Another day. Another check-up. Another drive that Jodi Larkin could make with her eyes closed if her 5-year-old daughter Lindsey wasn’t in the car.

Jodi walks out of their Oswego, N.Y., home and straps Lindsey into the back seat of their Dodge Caravan. She settles behind the wheel, puts the key in the ignition and starts to pull out of their driveway.

But before they leave, Lindsey rattles off a few questions.

Where are we going?…Are we going to the doctor?…Am I sick?

I don’t feel sick.

Jodi turns around to see her daughter, blonde hair bouncing with the engine, brown teddy bear clasped to her chest.

“We’re just going for a ride, sweetie,” she responds.

They go back and forth. Lindsey, always inquisitive, drilling her mom with question after question. Jodi, always careful, masking their destination as long as she can.

But as they come around a bend, Lindsey starts noticing a familiar landscape. She recognizes the highway, the Crowne Plaza — or as she calls it, “the round hotel” — and the Syracuse skyline.

“Are we going to my hospital, Mom?” she asks.

Sitting by a window in Goldstein Student Center 15 years later, Jodi looks out at the snow-laden SU Softball Stadium. She stares deep into the field that Lindsey now calls home, and tears up remembering the journey her daughter took to get there.

“It was really hard hearing your little girl refer to the hospital as ‘her hospital,’” Jodi said. “But that’s just how it was.”

Lindsey Larkin will be the first to tell you how much she cries, and show you how much she smiles.

The 20-year-old pitcher often finds herself speaking in cliches. They make her blush, trail her eyes to the ground or let out an awkward laugh. Sometimes laughter turns into tears.

But she grins more than she doesn’t — that’s the Lindsey everyone has always known.

“That kid was always beaming, and still is,” said Millie Sherman, Lindsey’s grandmother. “Sometimes I didn’t know how, but she really never stopped.”

Courtesy of Jodi Larkin

Always smiling but also intense. Lindsey started playing all sports at a young age and didn’t let her medical problems stop her from running around with everyone else.

Now a sophomore pitcher on the Syracuse softball team, Lindsey’s smile punctuates the story that hides behind it. A story that includes regular hospital visits from the time she was 8 weeks to 8 years old, a gastroenterologist, urologist, nephrologist, cardiologist, otolaryngologist, infectious disease specialist and pediatric surgeon.

A life-threatening allergy, a severe kidney reflux and a life-changing surgery that finally healed her, and the family that never lost hope or sight of a healthier future.

Yet when she’s asked about the eight years that now define her as a person and athlete, Lindsey squints her eyes. She racks through her brain and looks up, searching for anything that resembles a memory.

She finds it impossible to vividly recall a thing.

If you go through a traumatic experience such as being in the hospital until you're 8 years old, you don't really want to remember any of that.Lindsey Larkin

Dr. Manoochehr Karjoo’s voice bounced off the walls of the hospital room.

“Get this baby off milk. You are killing her!”

Lindsey was just 8 weeks old and, as her parents put it, lifeless at Crouse Hospital. She was initially scheduled for a five-day visit, but it took another six — with a spinal tap, numerous doctors and multiple research teams from Upstate Medical School — to find that a milk-protein allergy was on the verge of taking her life.

The Larkins had started giving her formula and the hospital was doing the same. The doctors had never seen this combination of side effects before.

But tests finally revealed that it was the protein in the formula that gave her high fevers, colitis, urinary tract infections and E. coli in her bloodstream.

“It was like two weeks of hell,” Jodi said.

That was the first time she survived. The doctors stabilized Lindsey and told the Larkins that she could never have milk, chocolate, ice cream or any other dairy products.

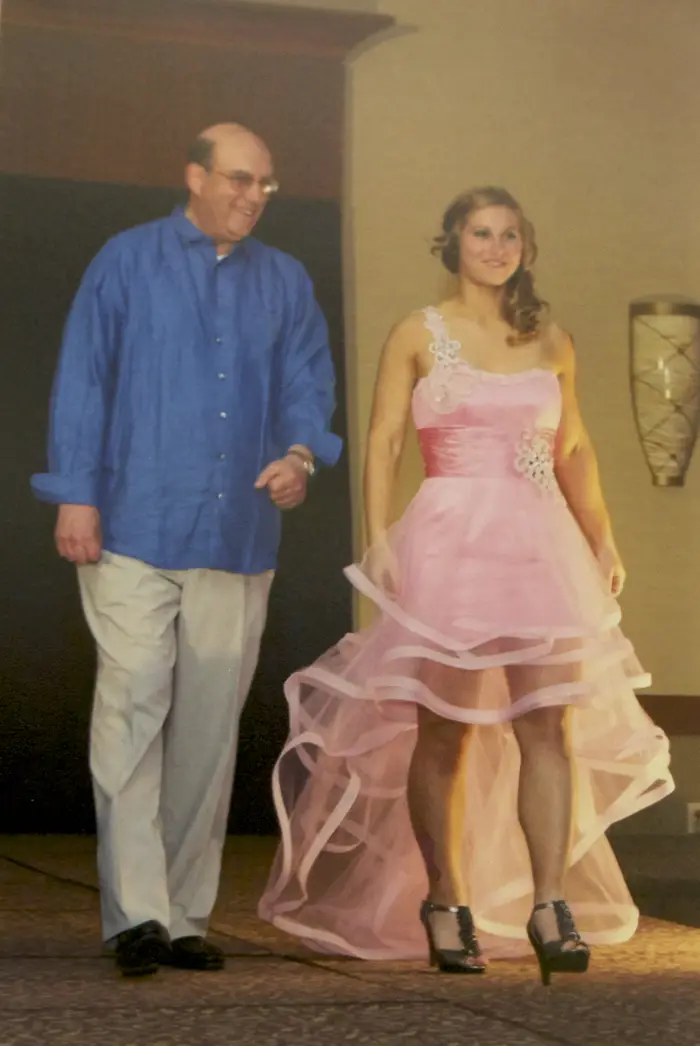

Courtesy of Jodi Larkin

When Lindsey was in the hospital, her family stayed at the Ronald McDonald House in Syracuse so they could be close to her. She started doing charity work with the organization as she got older, and here she is walking in a fashion show with Dr. Michael Ratner, a pediatric surgeon who helped her through her medical problems.

But somehow, she’d accidentally eat dairy and each time she did they’d be right back in the hospital where it all started.

“I vaguely remember hating that,” Lindsey said, “being a kid and just having to lay there.”

Then at a year and a half, the urinary tract infections returned. When they didn’t stop a year later, she was referred to Dr. Umeschandra Patil, an urologist and pediatric surgeon at Crouse.

Dr. Patil found that Lindsey had a severe kidney reflux caused by a birth defect. Her ureters — muscle fibers that propel urine from the kidneys to the urinary bladder — were undersized and her valve hadn’t developed. The reflux caused infections that destroyed function in both of her kidneys.

That’s when the hospital visits picked up — sometimes multiple times a week. When Lindsey would go to Crouse, Jodi and her husband, Cliff Larkin, would pack a bag of clothes to stay overnight.

They’d bring their son James, who is four years older than Lindsey, to Jodi’s parents down the street and try to return the smile to their bedridden daughter’s face.

When we went to the hospital, we never knew when we were coming back.Cliff Larkin

In 1999, the rate of Lindsey’s kidney loss was continuing and she needed surgery as soon as her bladder wasn’t irritated.

And on July 6, 2000, Dr. Patil performed a miracle.

Cutting a 10-inch incision from side to side, Patil built bigger ureters from Lindsey’s own body tissue. He formed them to fit her 6-year-old body, and so they would continue to grow as she did.

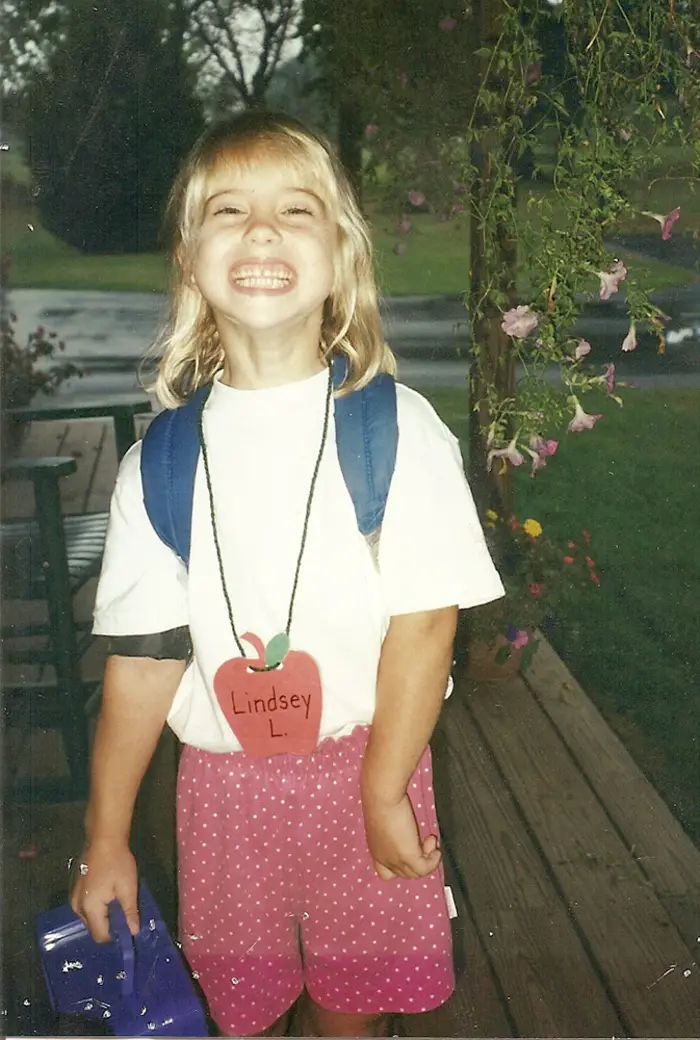

Courtesy of Jodi Larkin

Before the first day of Kindergarten Lindsey is all smiles. Her backpack is connected to the black strap on her right arm and monitors her blood pressure throughout the day.

Nothing could stop Lindsey from smiling on the first day of kindergarten. Not the early wakeup. Not the damp weather. Not the strap on her arm or the machine in her backpack that tracked her blood pressure.

“Can you see the black thing on my arm, Mom?” she asked, as she danced around the wooden porch, her apple name tag flapping off the white T-shirt that did little to hide the strap on her right elbow.

“Nope Lindsey, I can’t see a thing,” Jodi answered.

“Good!” Lindsey said, jumping off the porch as her backpack let out a low hum.

School was different for Lindsey. Around lunchtime, every day, she’d visit school nurse Lori Dempsey to have her blood pressure recorded and take medicine for her kidneys. If a classmate brought in cupcakes for a birthday, she’d have to decline.

But while she was watched closely by her parents and teachers, she also learned to take care of herself.

That's how I always knew her. The girl who needed the most attention of all the ones I baby-sat, really needed the least.Dolores Purtell, Lindsey's babysitter for many years

She fell in love with sports in grade school, and played them just like everyone else. She tried basketball, football, dancing and gymnastics — even though the last two make her cringe looking back — but fell in love with baseball.

Courtesy of Jodi Larkin

Lindsey started out playing baseball until she switched over to softball when they made a team for her to play on. She wasn’t happy at first, but then fell in love with the sport.

She played baseball with all the boys until she was 12 and the town formed a softball team for her to join. She was reluctant, but started garnering attention on the mound immediately after she made the switch.

“Once I got to regionals and I saw all the talent and saw how I did with those caliber of girls,” Lindsey said. “I thought playing college softball was actually an option.”

Then she zeroed in on that goal. When Lindsey was 13, she told her parents she needed a new pitching coach after the coach told her she’d never throw 60 miles per hour or play collegiately.

They obliged, and two months later she was putting 60s and 61s on the speedometer.

She started training with strength and conditioning coach Dennis Dewane at CNY Speed Training.

When he opened the gym in the morning, she would be there waiting for him. And when he closed it at night, she’d want to keep going.

In high school, Jodi would text Lindsey over and over asking if she’d be home for dinner. Lindsey’s phone was in her bag on the side of the G. Ray Bodley softball field, as Lindsey threw pitch after pitch into the backstop. No catcher. No coach. No one around.

Most nights, she’d heat up a plate of food while icing down her left arm.

“Even if she can’t remember all of it, her past and what she went through has everything to do with the hard worker she has become,” Jodi said. “It’s just inside of her that no one can tell her what she can or can’t achieve.”

Lindsey was just a freshman reliever and didn’t expect to pitch when Syracuse head coach Leigh Ross told her to prepare to take the mound in the team’s second home game last season.

Senior Stacy Kuwick had already gone six innings and sophomore Lindsay Taylor was sidelined with an injury. So heading into extra innings, Ross handed Lindsey the ball.

“She was nervous,” said SU pitching coach Jenna Caira. “I told her I wanted three things. I wanted a first-pitch strike, I want a strikeout and I want a ground ball.”

When Lindsey jogged out to the mound for the start of the seventh inning, tears started streaming down Jodi’s face in the stands.

Courtesy of Jodi Larkin

Lindsey trains in the Central New York snow, working on her strength and conditioning as part of her workout routine.

Lindsey threw a first-pitch strike and turned to Caira, a smile spread across her face.

Jodi kept crying, now shaking in her seat.

Then Lindsey got a ground out and looked at Caira again, her smile wider this time, her mom juggling the past with the present and standing to cheer for every out.

She may not have gotten the strikeout that Caira wanted, but after throwing four innings, Lindsey walked off the field with her first collegiate win.

“All I thought was ‘Lindsey, you’ve come so far,’” Jodi said.

Many years ago, when she looked out the back window of the Caravan at Syracuse, Lindsey’s head was full of questions. Her future was uncertain. Her health always the focus for her and her family.

But now when Lindsey drives toward the Adams Street exit and into the city that saved her life, she no longer wonders where she’s going.

Banner photo by Emma Fierberg | Asst. Photo Editor

Published on February 17, 2014 at 3:20 am

Contact Jesse: jcdoug01@syr.edu | @dougherty_jesse

Great photo, Emma! Someone should fix the caption on the photo of her first day of kindergarten. The black strap is on her right arm, not her left.

What a great and inspiring story!

God bless you Lindsey and your family. Your life story can be a blessing and a helping tool to so many people.

This is such a beautiful story. My daughter is a freshman pitcher for Rutgers University and I know how hard she worked to achieve her goal as a Division 1 pitcher. I can’t imagine going through what Lindsey went through medically, and still begin able to achieve her dream to play ball at a Division 1 program. All young/ high school athletes should read this inspiring story to help them to realize that if you work hard, nothing can get in your way of accomplishing your dreams … Even going through trauma and so many obstacles to overcome. Lindsey worked extremely hard to get where she is now, and she and her family should be very proud of her accomplishments ! My daughter just picked up her first collegiate win, and I know how exciting it was for her and all of us ! I’m glad her mother was there to share that big moment with her! I’m going to have my daughter read this article. Thanks for sharing and good luck to Lindsey in the future!

On behalf of our family, we’d like to thank Jesse Dougherty. We all had kind of put that behind us and moved on with our lives and really never looked back. When he first asked me last year about doing this story, we were all hesitant and said no. I am so glad he asked again. What Jesse did with all our most precious moments was beautifully written. It was hard to share but I am glad we did. If Lindsey’s story inspires even just one person to dream big and follow their dreams then every bit of it was worth it.

Enjoy life!

Having been on the (far) sidelines, watching this family; first, struggle with, and overcome, Lindsey’s health issues with grace and endurance; and then Lindsey’s fierce determination and passion to overcome any and all obstacles put in her way! ex. Not allowing coach “A” to have any negative impact upon her dream, where another may have simply thrown in the towel so to speak! While amazing as Lindsey is, many Kudos to Jodi and Cliff for doing whatever was necessary, exhausted or not, to ensure Lindsey every opportunity to reach her dreams and goals! Congratulations on your successful journey, live the dream!!!!!