Just after 3 p.m. on a Friday in September, a line of students stretched across three storefronts in Marshall Square Mall.

Some gripped Starbucks iced coffees. Others used their shirt sleeves to fight the humidity. All of them craned their necks to see how close they stood to the next head coach of the Syracuse men’s basketball team.

One by one, they walked up to Mike Hopkins as he offered a swinging high-five, an autographed photo and a personalized conversation.

Smack. “Were you at the six-overtime game or do you just have the shirt?”

Smack. “Where’d you get those shoes? Those are sweet.”

Smack. “How’s your freshman year going? You came a long way from Atlanta.”

A freshman boy was worried about the weather. “Is it really that bad?” he asked.

Hopkins’ eyes widened as he jumped into his own coming-to-Syracuse story. In 1988, he moved to central New York from sunny Mission Viejo, California to play basketball for the Orange. He had a full head of surfer-blonde hair, an unrelenting work ethic and was in pursuit of perfection. That’s how he went from JV athlete to Big East recruit. From benchwarmer to Syracuse captain. From Syracuse’s temporary head coach to the man who will take over for Jim Boeheim in 2018.

“Mike has truly earned this honor through his hard work, dedication and commitment to our program for more than 20 years,” Boeheim said when Hopkins was announced as his successor. “There is no one more ready or prepared to carry on the success of Syracuse basketball than Mike Hopkins.”

The transition started Saturday, and Hopkins’ voice quivered with emotion as he lamented not winning for his mentor. He was filling in for Boeheim for the first of his nine-game suspension stemming from an NCAA investigation. Twenty minutes after Syracuse fell to Georgetown, he stopped midsentence and took a long stare at the box score in front of him. When he looked up at a room crammed with reporters, his eyes were red and filling with tears.

I've been preparing myself to be a head coach for 20 years. That was always what I wanted to be. I always visualized myself doing it.Mike Hopkins

Hopkins doesn’t dwell on how long it took to get here; instead he remembers everyone who said he’d fail. He keeps three binders marked “Inspirational Quotes” in his office. He recently read a book titled “Onward: How Starbucks Fought For Its Life Without Losing Its Soul” to study a company’s success. He became Syracuse’s next head basketball coach by turning every experience into a learning opportunity, by turning every day into a step toward that dream.

In some ways, it all began with the purchase of an oversized coat when he got to Syracuse some 27 years prior. Hopkins reached out his arms to show the freshman from Atlanta just how puffy it was. Time, he explained, has acquainted him with the cold. Time has done a lot of things.

“Now it’s shoes, no socks, jeans and a light jacket,” Hopkins said to him. “When you’re here this long, you just adjust. You’ll be fine my man. See you at the games.”

Logan Reidsma | Photo Editor

• • •

It was 7 a.m. on a Saturday and, like any kid, Mike Hopkins was fast asleep.

But Griffin Hopkins, his father, had been awake for several hours. He started with a five-mile run, tidied up the house and was now washing the family cars while their California neighborhood stirred in the morning hush.

“I can’t believe your dad is out there and you’re going to lay in bed,” Mike’s mother, Sue, said through his bedroom door. So he peeled away the blanket, put two feet on the floor and followed his father’s lead.

Five days a week, Griffin woke up at 4:30 a.m. to drive 65 miles through Los Angeles traffic to his family-built business in La Verne, California. Then he’d drive 65 miles back, all so his family could live in the idyllic Orange County. He’d sometimes fall asleep at the dinner table but always helped his wife with the dishes at night’s end.

“He was just like a machine,” Mike said. “That’s where I learned it.”

Griffin signed Mike up for his first organized basketball team in the fourth grade, and Mike took to the game immediately with an unyielding tenacity. The skill it took to score, grit to defend, teamwork to win. He was the first player on his team to develop an actual jump shot because he realized other kids couldn’t block it.

By sixth grade, Mike was playing on an AAU team with two future NBA players, a college All-American and a gold medal Olympic sprinter. He played one-on-one with his friend Chris Patton — then rated the No. 1 high school freshman in the country — and would lose 50-1 in Patton’s backyard. They’d play again to the same result. And again, same result.

“I fell in love with basketball because my friends were all better than me,” Mike said. “And then it was, ‘How do I get better?’”

He arrived at Mater Dei (California) High School as a solid player dead set on becoming more. He played on the freshman team but stayed in the gym to watch the JV and varsity practice, studying players both good and bad. He refused to leave the gym until he won the last game of one-on-one. Late at night, he’d call one of the assistant coaches to discuss everything from his help defense to free-throw form.

And if he wasn’t shooting hoops, Mike glued himself to Big East games playing in primetime on the opposite coast. Patrick Ewing at Georgetown. Chris Mullin at St. John’s. Pearl Washington at Syracuse. He watched with friends and rattled off their names like he was opening a pack of baseball cards.

Mater Dei head coach Gary McKnight took Mike and a few friends to a Syracuse basketball camp after their freshman season. Though it wasn’t a recruiting trip, Mike treated it like one. And he fell in love.

“He came back and he told everybody that I’m going to go to Syracuse. He said, ‘I’m going to get a basketball scholarship,’” Paul Hoover, then a Mater Dei assistant coach, said. “And everybody laughed at him. I can remember people saying, ‘Yeah, sure you are Mike. Sure.’”

Three years later, Syracuse unveiled a strong recruiting class that featured Billy Owens, Dave Johnson, Richard Manning and a lanky kid from southern California. Mike, who stood 6 feet, 5 inches tall, had impressed Boeheim enough to earn a scholarship, but didn’t exactly figure into the Orange’s future plans.

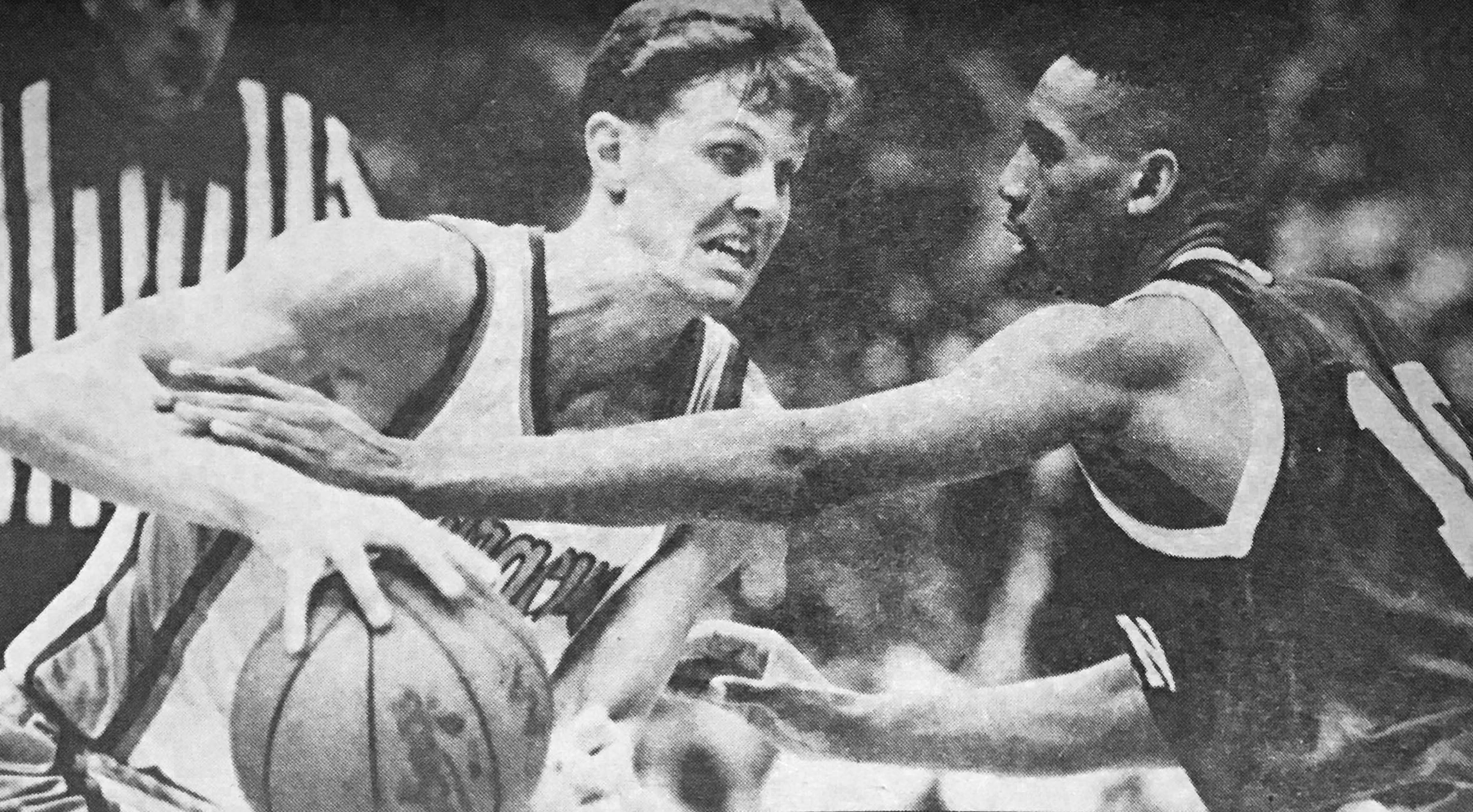

Daily Orange File Photo

He redshirted his first season, played sparingly the next and was just about done with Syracuse after logging 13 minutes per game as a sophomore. After the Orange lost to Richmond in the first round of the 1991 NCAA Tournament, Mike told Matt Roe what he’d been thinking all year.

“I don’t know if I’m ever going to play here; I think I have to leave,” Roe, who’d transferred from SU to Maryland two years prior, remembers Mike saying.

“And for a second,” Roe says now, “I thought he really meant it.”

With the season over, Mike took a trip home during a break from school. His father’s company had just opened a new plant and he wanted to give his son a tour. They had talked about transferring several times — over the phone, in the house, in the car — but now Griffin showed Mike the tangible reward of hard work.

When they got to PaperPak Product’s new offices, a security guard asked to see Griffin’s ID. He patted both his pockets and realized he’d left it in the car.

“Listen, my name is Griffin Hopkins and I work here,” he said to the security guard.

But the guard wouldn’t let them through without identification. They walked back through the plant, got his wallet from the car and approached the entrance.

“Mr. Hopkins I apologize … ” the guard started, realizing that he had been talking to the CEO.

“This is the type of person I want working for me,” Griffin responded. “You’re just doing your job at a high level and I’ll always remember that.”

Standing beside his father, Mike knew the key to getting on the court at Syracuse.

• • •

The church was quiet aside from the bouncing of the basketball.

Hopkins often went there with Leo Rautins, who played at SU in the early ‘80s before embarking on a professional career. Rautins later moved back to Syracuse, took a liking to the 20-year-old Hopkins and found himself with a key to Most Holy Rosary Parish on the city’s west side. So they came to the gym and took free throws, then jumpers, then broke into an all-out game of one-on-one.

Now the church was filled with voices, two of them, trash-talking each other while elbows flew and sweat dripped on the worn wooden floor.

“I used to talk a lot of (stuff) to him, try and get in his head, try and control him, try and do things like that,” Rautins said. “It was an effort to teach him how to do it.”

In Hopkins’ third active season, he teamed with Adrian Autry in Syracuse’s backcourt and used wit and will to become the team’s eccentric energy source. He regularly dove on the floor, pressed up on the opposition’s best players and was named a captain as a senior.

Away from practices and games, Hopkins itched for more and went to the church with Rautins. He and teammate Stevie Thompson knew what buttons to press in the Manley Field House security room to get in late at night. If they couldn’t, they ran down to the Women’s Building and played on a wooden backboard with an old-school rim.

He knew the late-shift security guard in the Carrier Dome, who would flick on the hallway lights to illuminate a path to the court.

Inside a dark, empty stadium, Hopkins took jump shots alone.

“Mike was a different breed,” said Autry, who now works alongside Hopkins as an SU assistant coach. “He just wanted it so badly. He didn’t stop and he figured it out. Having a guy like that, it gave us a certain edge, a swagger. We knew, within the program, how much Mike meant to our team.”

Daily Orange File Photo

After leaving Syracuse, his life was filled with injuries, plane rides and a fleeting goal of playing professional basketball.

It started in Denver, where he recalled being one of the last cuts off the Nuggets’ summer league team. Then he was days away from flying to Cyprus for what he said was a $35,000 contract before a last-minute change. Instead he trekked to Rochester, Minnesota, for a brief stint in the Continental Basketball Association.

Next was an international tour that included stops in Turkey, France and Holland. Eventually he decided to hang it up.

Back in Orange County, Hopkins thought about his next step. Two and a half years had passed, and he needed a direction. He wanted to work for his father, but Griffin had just laid off six employees after coming off a bad financial year. He didn’t think it would be right to hire his son in their place, so Hopkins sunk into his couch, bag of Doritos in hand, and watched hours of O.J. Simpson coverage to pass the time.

Knowing that your career is over is depressing enough, and now my dad can’t hire me so now it’s like the double depression shot of espresso at Starbucks. The double shot of misery.Mike Hopkins

Naturally, he turned to basketball. Hopkins called an old coach and started giving personal lessons. Soon he had a dozen players and was coaching an AAU team. He thought he may be onto something. Then the phone rang.

“Listen, I think I’m going to get the Duke job. I think you’d be a great coach,” said Tim O’Toole, an assistant at Syracuse. “You should call Coach Boeheim and tell him you’d want my spot if I get the job.”

O’Toole was right about two things: He was hired as a Duke assistant, and Hopkins had a knack for teaching. Hopkins called Boeheim and, like he did eight years prior, flew out to Syracuse to help his former coach with a camp.

He hasn’t left central New York since.

“Every star was aligned,” Hopkins said. “The way it happened was incredible.”

• • •

Gerry McNamara stretched out his arms and legs, picked up a basketball and started walking toward the basket on the far side of Syracuse’s practice court.

He’d worked out with Hopkins, an assistant coach then in charge of the guards, from the start of his career in 2002, and here he was again in an empty gym.

As he crossed half court, the junior guard noticed two pieces of tape stuck to the floor. The first one, about 8 feet behind the 3-point line, read “J.J.’S RANGE.” The second, 4 feet in front, read “G-MAC’s RANGE.”

Hopkins wanted to remind McNamara of Duke’s J.J. Redick, who was making national headlines and averaging 21.8 points per game. McNamara smiled, shook his head and started launching 3s.

“I couldn’t wait until he got out there because I was going to give him quite a face full of stuff,” McNamara said. “He had a way of getting under your skin in the perfect way.”

From the time he started as an assistant in 1996, Hopkins’ creativity and non-stop energy made him a skilled motivator.

When Ryan Blackwell was slumping in 1998, he called the sophomore into his office and showed him a highlight tape of his best plays that Hopkins compiled himself. He offered to come early and stay late for any player, to help them “figure it out” like he had, in the darkness of the Carrier Dome so many years ago.

Allen Griffin took him up on that, dozens of times, and Hopkins dove after his misses so they wouldn’t hit the floor. When Griffin’s girlfriend gave birth in December of 1998, Hopkins sat patiently in the Crouse Hospital waiting room.

For him to be there for me the way he was, all the time, it’s something I will cherish for the rest of my life.Allen Griffin

Hopkins began as a restricted-earnings assistant who wasn’t allowed to recruit. That afforded him opportunities to get close with the players and immerse himself in opponent scouting. When he started on the recruiting trail around 2000, he drove with his pregnant wife up and down Interstate 81 to seek talent in SU’s backyard.

Working with fellow assistant Troy Weaver, Hopkins’ first class included Craig Forth, Billy Edelin, Josh Pace and Hakim Warrick. The next featured Gerry McNamara and Carmelo Anthony. In the spring of 2003, those six players formed the nucleus of Syracuse’s only national championship team.

“Hop is a guy who can take a kid, whether it’s a kid at the end of the bench or a kid who plays a lot, and he’ll make them feel special,” said Jim Hart, who coached Forth in AAU. “As a coach, you want to send your kids to play for a guy like that. He was so trustworthy as a recruiter.”

His eye for talent and ability to develop it made him a hot coaching candidate in the coming years. He was connected to the University of North Carolina at Charlotte job in 2010, Oregon State in 2014 and a handful of other opportunities. He says he interviewed for some, declined others and always had the same rebuttal when schools talked badly of the Syracuse weather.

“It’s always warm in the Carrier Dome,” he’d tell them.

In 2013, Hopkins said he was nearly hired at USC before the Trojans chose Florida Gulf Coast’s Andy Enfield. He was disappointed he wouldn’t get closer to home, but Syracuse was where every opportunity had originated. Boeheim hired him without any experience, took him to work with the U.S. Olympic team and had already said he wanted Hopkins to take over for him when he retired, whenever that would be.

“Life is unpredictable, you never know what’s going to happen,” Hopkins said. “Live for the day, try and prepare the best for the day.”

He was officially named the Orange’s “head-coach-in-waiting” in June.

Logan Reidsma | Photo Editor

• • •

In October, Hopkins placed his MacBook Pro on his office desk.

He flipped it open and pulled up 15 years of photos and videos organized by date. His eyes lit up. Memories flooded back.

“I need to look at this all more often,” he said to himself. “Man, look at this stuff.”

There was his son Griffin’s first time at Yankee Stadium. A video of him working on Demetris Nichols’ jump shot. A photo of his dad and brother smiling in the Carrier Dome stands. A shot of him and Derrick Rose, arm in arm at USA Basketball camp, after he and a handful of NBA stars got McDonald’s after a late-night workout.

Next there will be photos from Saturday’s game. Then from his first season as a head coach. And then … who knows.

He scrolls through the years and starts connecting the dots. From childhood to perfectionist, from player to coach, from failure to success. This is how he got here. This is how he became the next head coach of a program that was once 2,700 miles from home and even farther from reality.

It’s all right there on the 15-inch screen, proof of what the world has already seen.

“When I first started coaching, my goal wasn’t to be the head coach at Syracuse,” Hopkins said. “My goal was to be the best coach on the planet. I just wanted to be the best.”

Sam Maller | Staff Photographer

Banner photo by Sam Maller | Staff Photographer

Published on December 6, 2015 at 11:31 pm

Contact Jesse: jcdoug01@syr.edu | @dougherty_jesse

You must be logged in to post a comment.

What a fabulous profile!!

Great read!

That’s exceptional journalism. Makes me proud to be a DO alum.